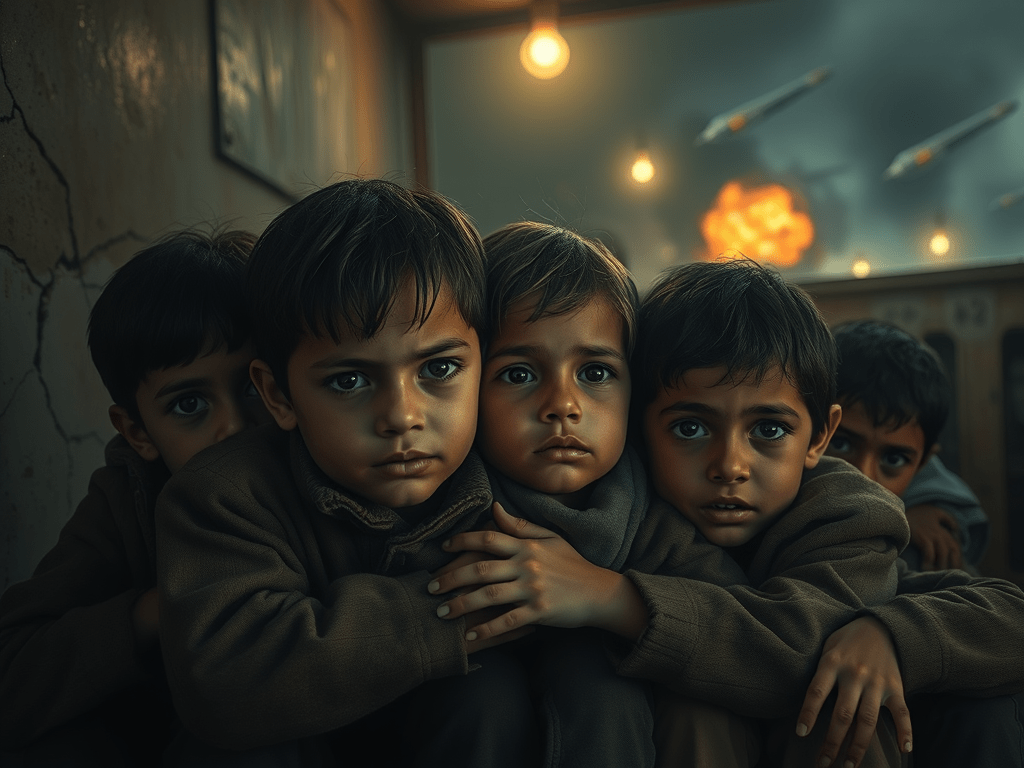

The noise never truly stops. For children, the war between Iran and Israel isn’t something they read about or hear discussed in passing—it’s the sirens that yank them from sleep, the trembling ground, the walls trembling around them. The sudden roar of missiles overhead and the sharp crack of defensive interceptors have shattered the illusion of safety. Each explosion brings the terrifying possibility that their homes, their schools, their playgrounds may be the next target. Simple joys like coloring on paper, playing tag, pretending to be astronauts—all of these are overshadowed by fear. That fear is endless and overwhelming, yet they learn quickly: this is the new normal.

Imagine being six or seven, a young mind still shaping its understanding of right and wrong, goodness and evil. Now imagine that your bedtime stories are interrupted by the blare of alert sirens. You hide not just from common fears like the dark but from something nameless, unstoppable, a force that says “run.” Even if you’re tucked under a concrete slab in a public shelter, that’s not safety. It’s not home. It’s cold. You might be lying next to strangers, listening to someone’s child cry, feeling the floor shake with each explosion. Those nights stretch longer than they should, each tick of the clock echoing with “What if.”

In Israel, attacks have come swiftly and without warning. Iranian missiles have hit cities such as Tel Aviv, Haifa, Bat Yam, Rehovot, Rishon LeZion, and Tamra, striking civilian areas and killing children—there’s even record of attacks on an 11‑year‑old boy and a 9‑year‑old girl in Bat Yam . Every strike involves more than casualties—it takes away the possibility of peace, of a predictable tomorrow.

In Iran, young families are fleeing Tehran in a rush of fear. Tens of thousands of residents have left their homes in mass exodus, including families with small children. They load whatever they can into cars, sometimes without enough fuel, driving through roads choked with panic. One refugee account captures it: “I left Tehran for Kerman… Fuel was rationed… each person is allowed only 25 litres…and at every gas station we had to beg and plead… heavy traffic… road to Qom …was bombed”. Parents hold their children close. Some cannot leave—the elderly, the sick, those trapped without transport. Everyone is vulnerable.

Traveling north from Tehran, families reach small towns and villages. Refugee centers are overcrowded and under‑resourced. No one plans for this. The food supply is limited due to roads being dangerous or destroyed. Prices have doubled or tripled in just days—rice, chicken, meat, fruit are scarce and expensive; dairy is up by a fifth. Can families with young children afford to buy milk, let alone nutritious meals? They don’t have a choice. Yet they try—their little kids are thirsty, hungry, scared.

Schools have closed on both sides. In Israel, they are shut down because nobody knows when the next wave of missiles will come. Parents struggle to work remotely and care for children who desperately miss classmates, teachers, routine. Children learn best in chaos-free environments; this war has filled every corner with chaos.

In Tehran, connectivity is unreliable. The internet is slow or gone due to strikes, making it impossible for children to learn remotely. Parents can barely check in with relatives, let alone help kids with schoolwork. The few who can voice their fears publicly say, “I’m constantly afraid a missile might hit my home… My life has been thrown off routine… I spend most of my time just reading the news”. That’s a parent. Imagine being the child who watches them.

Mental health is fragile, especially in times like these. Therapists warn that children exposed to repeated trauma are at risk for long‑term psychological harm: anxiety disorders, PTSD, depression. They may stop speaking about their emotions, may regress—bedwetting, nightmares, sudden aggression, withdrawn behavior. These are not just emotional responses—they are physical wounds hidden beneath the surface. The world owes them more care than a passing mention in news reports.

Children’s suffering is not limited to what they see and hear. In the scramble for evacuation, some are left behind. Families fleeing Tehran mention that if you don’t have a car or money or a place to go, you stay. That means children stranded without shelter, without safety, possibly without food or medical care. The collapse of infrastructure means no buses, trains, flights. Mothers with infants, children with chronic illness—these are the most vulnerable.

Camps in Kerman and other cities are flooded. The Iranian Red Crescent has deployed mobile clinics to major highway junctions. Yet these are temporary solutions when what’s needed is permanence and protection. A place where children can be children again—learn, laugh, play, sleep. Where they aren’t searching for food or afraid of the next strike.

The statistics are heart-wrenching. In Bat Yam, homes destroyed, families torn apart. In Rishon LeZion, two civilians died and over 20 injured—including a rescued three‑month‑old baby. Entire city districts have been shattered. That’s lives. Each figure is someone’s child, someone’s sibling, someone with hopes and dreams.

Thousands are evacuated within Israel too—over 5,000 families, many with children, have been uprooted. They sleep in hotels paid for by the state, but that’s a temporary shelter too; children miss their rooms, their toys, the weight of blankets they chose themselves. Even a week in a hotel feels like exile. The parents are exhausted; the kids feel lost.

In both countries, services for children—schools, playgrounds, libraries, after‑school programs—are paused. Healthcare is diverted to treat wartime injuries. Mental healthcare is stretched thin. In Iran, inflation and food scarcity mean kids may go to bed without enough dinner. In Israel, workers in essential industries are on duty, but volunteers helping families are thin. A mother spoke about working from a park because schools are closed and sirens ring at any moment. A normal day for her is beyond stress—it’s survival.

It’s hard to imagine small children understanding why this is happening. They might watch the nightly news with frightened eyes, repeating phrases they don’t fully grasp: “evacuation,” “interception,” “missile defense,” “nuclear facility.” Those words become their vocabulary of fear. A four‑year‑old might ask: “Why is the sky loud?” or “Are we safe?” The answer adults give them is confusing because adults don’t have easy answers either.

Human rights groups have called out the civilian toll on both sides. Yet in media coverage, numbers race across screens; stories about children’s trauma get lost in geopolitical analysis. But behind each statistic is a child struggling to sleep, crying in a shelter, grinding through flashbacks in their dreams. Behind each evacuation log is a family that taught their child to run, to crawl under tables, to stay quiet—skills no one should need.

What can be done? At a basic level, immediate humanitarian corridors must be established. Children need safe zones, medical attention, psychological first aid. In Iran, fuel rationing must be eased for evacuees. Food and medicine must be available; mobile clinics must be scaled up. Psychological care must be prioritized; volunteers trained in child trauma should be deployed.

In Israel, schools should be converted into bomb‑resistant learning centers or underground classrooms. Shelters at homes are not enough. Parents need structured support—childcare helpers, counseling, financial help for displaced families.

Media and NGOs must spotlight children’s voices, not just mention them. We should hear from kids—through art, writing, video. We should share their stories so that the world cannot look away. If they speak of nightmares or the loss of a toy, we listen. We act.

International aid agencies and governments must treat this as a crisis of childhood. Too often, children are “collateral damage.” But these kids are not collateral—they are human beings. Provide toys, art materials, soft blankets. Give them spaces to play. Even a simple tent with coloring pages matters. Stability is more than food and shelter—it’s the possibility of being a child in the world again.

And afterwards? When bombs stop, reconstruction must include rebuilding schools, playgrounds, libraries. Children need that more than statues or grand monuments. They need the laughter of peers, the soft swing of a playground, the whisper of turning pages in a school book. Without those, recovery is never complete.

Parents watching on both sides carry guilt too. They ask: Could I have left earlier? Could I have stayed? Could I have hidden them better? They need support, and part of that is knowing the world is with them. They need to know that when this ends, they deserve rest. Their children deserve futures.

No one here sees the future as easy. The war is indiscriminate, costly, unpredictable. Yet in the midst of this violence, small acts matter. A teacher reading a story aloud in whispers at a shelter, a neighbour handing a blanket to a shaking child, volunteers giving out hot cocoa—these moments are lifelines. They remind children that the world can be gentle.

If history teaches anything, it is that children’s traumas linger unless recognized. Left unaddressed, childhood terror becomes broken adulthood. So every country, every aid group, every neighbour must do more: prioritize the children. Not based on nationality, religion, or politics—but because they are children.

Imagine them again. A little girl clutching a teddy bear, waiting for the next siren to pass. A boy with crayons hidden in his pocket, sketching a house that stands undamaged. A mother humming lullabies she learned as a child, to keep her baby calm when the world is loud.

That’s what matters now. Keeping those images alive. Turning them into real help: shelters stocked with snacks and crayons; doctors with training in child psychology; safe corridors for families to flee; classrooms in basements. We must act fast, because childhood doesn’t wait.

In the end, children should remember this time not only for the fear, but for the kindness they encountered. For the grown‑ups who shielded them, held them. The strangers who offered a toy, a blanket, a hot meal. They must remember that amidst the rumble of war, there were voices that said: You matter.

So that in fifty years, when they tell the story, they can also say, “There were people who cared, and we were worth saving.”

Disclaimer

This post is based on widely reported events, shared personal stories, and the lived experiences of families caught in conflict. It is not a news report, but a reflection on the impact of war on children.

Sources & Further Reading

- “Residents of Bat Yam emerge after deadly Iranian missile attack”

- “Two more victims of Bat Yam missile impact named, one thought to still be under rubble”

- “Ten Israelis, including two children, killed in Iranian missile strikes”

- “June 2025 Iranian strikes on Israel” (Wikipedia overview)

- Coverage on missile barrages and civilian toll (Reuters/AP)

- “Wards ‘completely demolished’ after Iran hits hospital”

Hi , I do believe this is an excellent blog. I stumbled upon it on Yahoo , i will come back once again. Money and freedom is the best way to change, may you be rich and help other people.

LikeLiked by 1 person